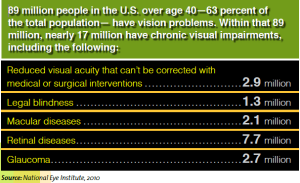

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was passed into law in 1990 to give persons with physical or mental impairments the same freedoms and abilities to live, work and play in our country as those without these impairments. When it comes to our buildings, the act requires commercial buildings and public accommodations be designed, constructed or altered so they are physically accessible to those with disabilities. Among its considerations, ADA provides guidance to accommodate individuals who are legally and totally blind, but it neglects 89 million people over the age of 40 in the U.S. (63 percent of the total population) who have vision problems, 17 million of which have chronic vision impairments, including macular and retinal diseases and glaucoma.

About five years ago, James E. Woods, Ph.D., P.E., an indoor environments consultant, was reviewing HVAC systems and completing post-occupancy evaluations for the Washington, D.C.-based U.S. General Services Administration. Accompanied by Stuart L. Knoop, FAIA, a design architect, and Vijay Gupta, P.E., GSA’s chief mechanical engineer (now retired), the trio began discussing this ADA oversight specifically in regards to how our buildings are lit.

About five years ago, James E. Woods, Ph.D., P.E., an indoor environments consultant, was reviewing HVAC systems and completing post-occupancy evaluations for the Washington, D.C.-based U.S. General Services Administration. Accompanied by Stuart L. Knoop, FAIA, a design architect, and Vijay Gupta, P.E., GSA’s chief mechanical engineer (now retired), the trio began discussing this ADA oversight specifically in regards to how our buildings are lit.

Gupta has a retinal disease. He is legally blind and is more sensitive to contrast and glare than a person with normal vision. Woods who has a background in teaching mechanical engineering and architecture also has taught lighting design and designed color-intensive lighting projects during his career. Woods’ lighting background and interest and Gupta’s personal sensitivity to light and glare prompted them to explore whether any lighting design guidance is available that considers building occupants with low vision.

They discovered current codes and standards, including ASHRAE 90.1, base lighting levels and lighting power densities on the needs of normally sighted people. The Lighting Handbook, 10th Edition, published in 2010 by the New York-based Illuminating Engineering Society (IES), is the first lighting design guideline to recognize the aging population has a different visual perception and, therefore, different lighting requirements, but the handbook’s recommended lighting levels are not based on empirical studies that include aging or low-vision persons.

Consequently, Gupta approached the National Institute of Building Sciences (NIBS), Washington, about hosting a workshop dedicated to low-vision lighting design. NIBS, a non-profit, nongovernmental organization authorized by Congress to bring government representatives and building industry professionals together to identify and resolve construction issues, hosted the workshop in 2010 and ultimately created the Low Vision Design Committee in 2011.

Woods, who was appointed the committee chair; Knoop, who was appointed committee vice-chair; and the 20 committee members, which include representatives from the architectural, engineering, lighting design, interior design, ophthalmology and optometry communities, have begun working on a design guideline—primarily for commercial and institutional buildings—to benefit all people but with a focus on accommodating those with visual impairments. The committee, which is liaising with organizations like IES, hopes to have a draft

of “Design Guide for the Visual Environment” available for public review by the end of this summer.

retrofit spoke with Woods about the design guideline, what makes it different from current guidelines, and how the new guideline may change the materials and methods we use to light our buildings.