The foundation, which incorporates sluiceways for canals once used to power milling equipment, had been ravaged by water damage. This undermined entire masonry walls. The preservation of the iconic clock tower, for example, required its complete removal from the building while the walls beneath were disassembled and rebuilt. The restored clock was then craned back into place. Also, once structural repairs were made, the team was able to install a low-head hydro turbine to harness the natural movement of the waters through the canal, which produces electricity for the grid.

Boott Mills’ beautiful brickwork presented an enormous challenge. For example, lightning had struck the 200-foot chimney, the construction of which included decorative work with bricks placed at 45-degree angles. Masons had to clean and replace the bricks while hoisted by crane into a precarious position high above the factory roof. The masonry was cleaned with a gentle wash, an old historical method used to preserve color and integrity, rather than sandblasting or harsh chemicals.

For the brick façade, the team tested the lime mortar and replicated its composition (the sand-to-lime ratio, at least). Then, to attain the crisp look of the original masonry, the weathered, rounded corners of the brick exterior had to be addressed. The team used tuckpoint method to fill up to 1/4 inch of each joint, achieving a uniform thickness across all joints in the façade, recreating the look of new brick.

Meanwhile, the design and construction team replaced 40 percent of the beams and floor decking in the mill buildings. After a year of design and development and 19 months of construction, the team completed Phase One in November 2005.

To Marry History and Development

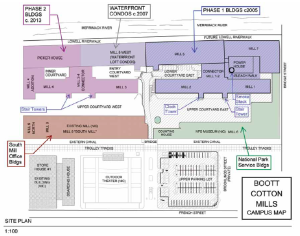

in 2005. Phase Two, which was completed in December 2013 and took just under three years, not only increased the numbers of rental units, but also incorporated 45,000 square feet of commercial space. IMAGE: The Architectural Team

Throughout the project, TAT and the development team worked closely with the Lowell Historic Board (LHB). The team brought its plans for Phase Two to LHB early on, knowing the body to be diligent and thorough. Phase One had been so well received, LHB told the team to consider it a template for future work. However, the team’s planning would be complicated somewhat by the development of 39 condominium units—the Waterfront Lofts— within a building on the Boott Mills campus by an unrelated design and construction team. The lofts project proceeded without comprehensive attention to historic views of the buildings, light fixtures, and details of windows and doors—issues that TAT would have to remedy as an addendum to Phase Two while the condo units remained occupied.

WinnDevelopment, now joined by co-developer Rees-Larkin Development LLC, Boston, planned for Phase Two to not only increase the numbers of rental units (all 154 from Phase One were by then occupied), but also broaden the portfolio of unit types and rent values. Plans to incorporate 45,000 square feet of commercial space qualified the project for a “new markets” tax credit that drove this phase financially. The scope of the second phase included five conjoined mill structures, considered one single structure under applicable building codes, plus remedies for the Waterfront Lofts building.

More challenges cropped up: All construction operations had to take place within the narrow confines determined by the river and adjacent canals. Also, there would be even greater scrutiny than with most historical projects because the NPS offices and museum face the project buildings. Exacting work to restore the façades and windows had been completed under NPS direction 20 years previously, and those details would need to remain undisturbed by the new construction.

The team also had to shore up the mill structures for seismic and wind-uplift requirements. For example, the team built girdles around the exteriors of the walls using a steel angle bolted to the top of every beam. Tens of thousands of square feet of open mill floor and defunct office space were completely gutted down to the base structure to make room for the construction of market-rate residences. Common spaces and amenities already in place for the condominiums had to be adapted and, in a few cases, fully reconstructed to make them work for the combined 117 units.